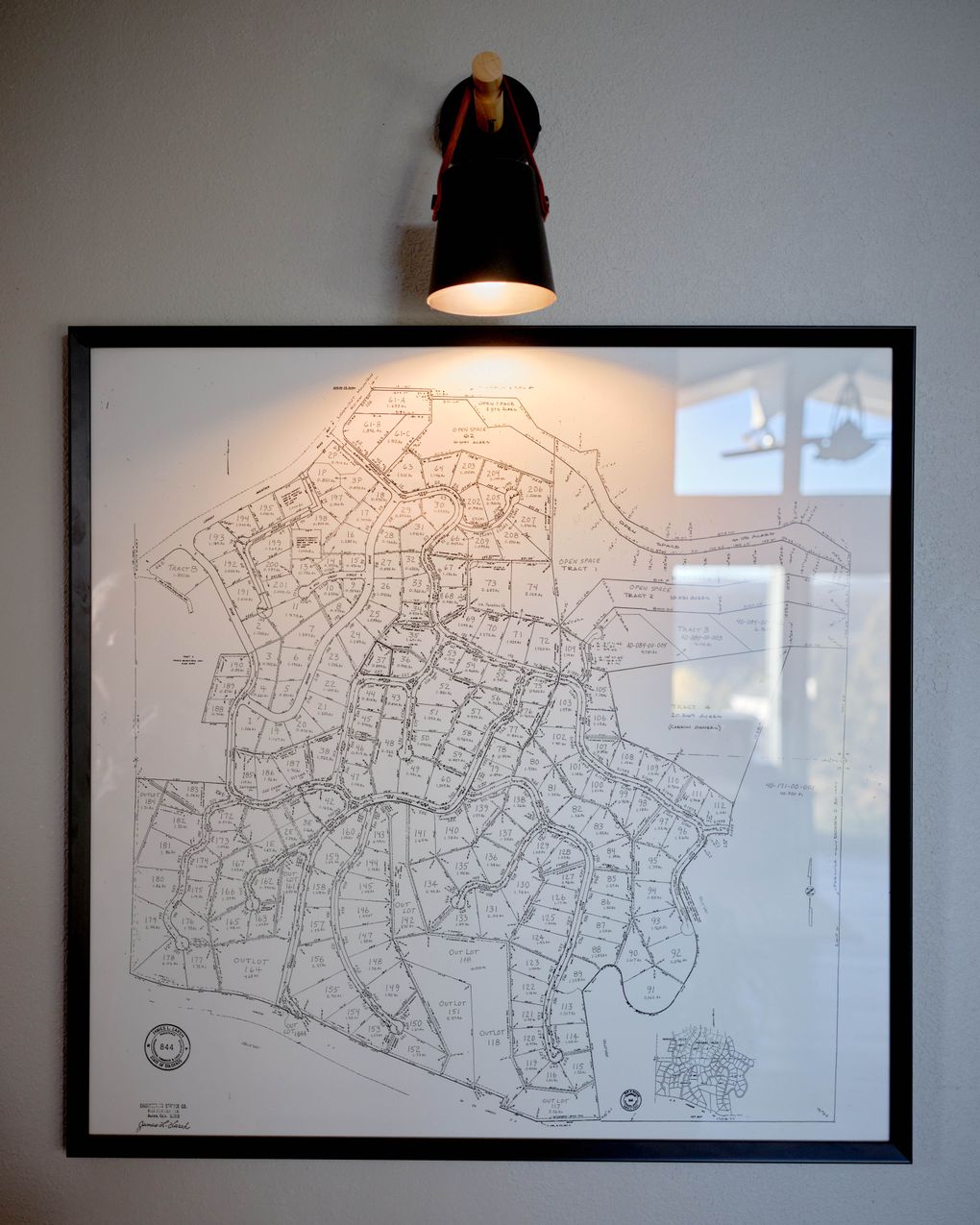

The Paradise Hills neighborhood sits in the quiet foothills of Golden, Colo., and its homeowners association traditionally has concerned itself with enforcing rules around garage door paint colors and nudging residents to critter-proof their trash.

So it came as a surprise to Skip Erickson when the HOA board this spring declared that its neighborhood was now besieged by crime, with “bullets flying,” street racing and burglaries “terrorizing the families.”

To address the threat, the board said it wanted to buy one of the country’s hottest new security tools: license plate readers built to scan the tag on every passing vehicle for later inspection by homeowners and police.

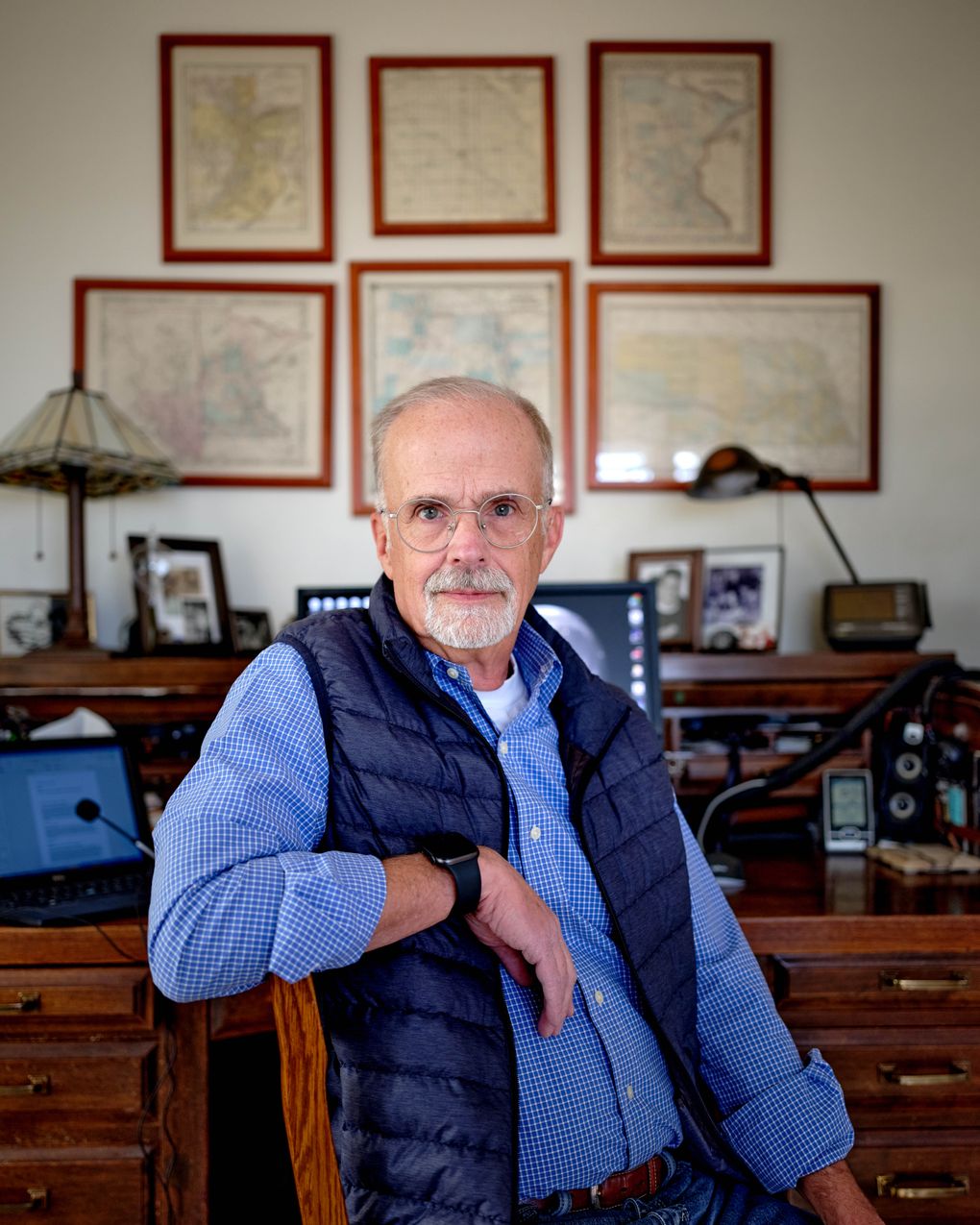

To Erickson, 71, the idea of recording everyone’s movements in hopes of combating some imaginary menace seemed invasive, ineffective and absurd.

“Usually, the car break-ins here are from bears, as opposed to people,” he said. “And yet suddenly there was this paranoia that we had to protect the neighborhood at all costs.”

License plate readers are rapidly reshaping private security in American neighborhoods, bringing police surveillance tools to the masses with an automated watchdog that records 24 hours a day.

With “safety-as-a-service” packages starting at $2,500 per camera a year, the scanners are part of a growing wave of easy-to-use surveillance systems promoted for their crime-fighting powers in a country where property crime rates are at all-time lows.

Once found mostly in gated communities, the systems have — with help from aggressive marketing efforts — spread to cover practically everywhere anyone chooses to live in the United States. Flock Safety, the industry leader, says its systems have been installed in 1,400 cities across 40 states and now capture data from more than a billion cars and trucks every month.

“This is not just for million-dollar homes,” Flock’s founder, Garrett Langley, said. “This is America at its core.”

The explosion of such systems, however, has created a new point of friction between crime-fearing residents and their privacy-minded neighbors, who note that by cataloguing time-stamped photos of every car’s comings and goings, the systems can generate a revealing portrait of drivers’ daily routines — residents and strangers, alike.

Adam Schwartz, a senior lawyer at the Electronic Frontier Foundation, said the digital rights group has fielded many calls from people concerned about the tracking systems being installed close to home.

“It does, frankly, create new public safety problems when you put powerful surveillance tools in the hands of untrained people who are fixated on local crime,” he said.

In Paradise Hills, a neighborhood of 185 homes in the Denver suburbs, a bitter debate over the system’s risks sparked fury in the community’s meetings and on its sidewalks, including a shouting match between a former board member and a camera-skeptical couple who had been walking their dog past his yard.

Both groups saw the debate as a microcosm of a polarized America, where everyone was angry and afraid all the time, and where no issue could be resolved without a fight.

The neighborhood’s camera opponents argued that the systems were a pointless, Orwellian annoyance they didn’t want greeting them every time they drove home. To them, the cameras felt like another step toward mass suburban paranoia, where every once-forgettable slight is now recorded by Ring doorbell cameras, shared on Facebook and discussed endlessly on Nextdoor.

But the cameras’ supporters said they felt mystified by all the resistance. Going soft on crime could put their families at risk, they argued – and no one on public roads should expect privacy, anyway. If their opponents weren’t criminals, what did they have to hide? Who wouldn’t want to feel safer?

The April announcement from the homeowners board said the newly convened “safety committee” wanted the two Flock cameras to monitor vehicles driving on Paradise Road, the neighborhood’s main entryway and a connector for nearby tourist spots like the Enchanted Forest Trail and the Buffalo Bill Museum and Grave.

The email included a nine-page packet prepared by the board and filled with Flock marketing materials, clippings of crime headlines from local news outlets, and a graph showing that traffic along Paradise Road had climbed from 3,000 vehicles a day two decades ago to roughly 3,500 today.

The yearly cost — $5,000 for the cameras, plate-analyzing software and online services — would be taken from the community’s fence-painting budget, the email said. And the board wanted the cameras up and rolling before the summertime hordes headed their way.

The scanner they chose was Flock’s main reader, the Flock Safety Falcon, which looks like an oversize sunglass case and was designed to blend in with the roadside gizmos drivers pass every day.

Its solar-powered, motion-sensing camera can snap a dozen photos of a single plate in less than a second — even in the dark, in the rain, of a car driving 100 mph up to 75 feet away, as Flock’s marketing materials say.

Piped into a neighborhood’s private Flock database, the photos are made available for the homeowners to search, filter or peruse. Machine-learning software categorizes each vehicle based on two dozen attributes, including its color, make and model; what state its plates came from; and whether it had bumper stickers or a roof rack.

Each “vehicle fingerprint” is pinpointed on a map and tracked by how often it had been spotted in the past month. The plates are also run against law enforcement watch lists for abducted children, stolen cars, missing people and wanted fugitives; if there’s a match, the system alerts the nearest police force with details on how to track it down.

License plate readers installed on highways, bridges and tow trucks have been used for years by federal agents, state traffic authorities and local police. They’ve played a role in rescuing kidnapped babies, tracking down U.S. Capitol riot suspects and pursuing undocumented immigrants. But Flock’s founding, in 2017, helped adapt vehicle surveillance for the general public, offering residential installations, consumer-friendly interfaces and advertising tailored to a suburban clientele. (Flock’s main competitor, Vigilant Solutions, sells primarily to local governments and police.)

Langley, a former electrical engineer who launched the company after some break-ins in his Atlanta neighborhood, points to FBI data that shows U.S. police agencies only closed 17% of reported property crimes in 2019 — “a pretty obvious failing grade” — as a sign that law enforcement needs enhanced surveillance to make America truly safe.

He argues the solution to crime is “quite simple”: more cameras on the streets. That means more evidence for the police, and more people afraid to commit crime. The company has pledged, perhaps implausibly, that by boosting the “presence of capable guardians” it can reduce crime by 25% nationwide over the next three years.

“Are we going to stop homicides? No, but we will drive the clearance rate for homicides to 100% so people think twice before they kill someone,” he said. “There are 17,000 cities in America. Until we have them all, we’re not done.”

Flock’s customer base has roughly quadrupled since 2019, with police agencies and homeowners associations in more than 1,400 cities today, and the company has hired sales representatives in 30 states to court customers with promises of a safer, more-monitored life.

Company officials have also attended townhall meetings and papered homeowners associations with glossy marketing materials declaring its system “the most user-friendly, least invasive way for communities to stop crime”: a network of cameras “that see like a detective,” “protect home values” and “automate [the] neighborhood watch . . . while you sleep.”

Along the way, the Atlanta-based company has become an unlikely darling of American tech. The company said in July it had raised $150 million from prominent venture capital firms such as Andreessen Horowitz, which said Flock was pursuing “a massive opportunity in shaping the future.”

Flock says its systems have helped police solve hundreds of murders and violent crimes, recover thousands of stolen vehicles and seize hundreds of illegal weapons. The company says it gathers its numbers based on “reports and anecdotes” from law enforcement customers, but all of the cases can’t be independently verified, and the company’s assertions that crime has plunged in some customers’ neighborhoods often give little mention to other factors that might have contributed — such as the covid-era closures that kept people home.

Flock deletes the footage every 30 days by default and encourages customers to search only when investigating crime. But the company otherwise lets customers set their own rules: In some neighborhoods, all the homeowners can access the images for themselves.

When former Paradise Hills board member Michele Lawrence heard some of her neighbors wanted to install license plate scanners, she was stunned. Were they really this paranoid?

The area’s rugged splendor had in recent years shown signs of modern growth, and longtime residents of the upper-middle-class neighborhood had begun regarding the influx of new tenants with increasing suspicion.

Her neighbors kept sending around videos from the cameras installed in their doorbells, windows and roof overhangs: a thief rifling through a truck; a stranger walking along a property line; a video of gun shots — or was it a car backfiring? — somewhere out in the dim moonlight.

“You would think we were living in a war zone,” said Lawrence, 55. “We have neighbors who have fortressed their houses in Ring cameras, and it’s gotten them nowhere — and nothing, except this false sense of panic. It creeps me out.”

Lawrence and other homeowners believed the Flock proposal had been rammed through too quickly; past debates about where people could install small backyard greenhouses had taken months. And they worried that this call for hyper-vigilance was obliterating legitimate questions about how the system could be used to promote vigilante behavior or spy on neighbors and passersby.

We’re “reacting to individual residents’ perceptions about criminal activity as opposed to the facts,” Erickson wrote in one email. The HOA, he added, “cannot become an arm [of] law enforcement.”

Camera opponents also worried about the consequences of the cameras getting it wrong. In San Francisco, police had handcuffed a woman at gunpoint in 2009 after a camera garbled her plate number; another family was similarly detained last year because a thief had swiped their tag before committing a crime.

And last year in Aurora, 30 miles from Paradise Hills, police handcuffed a mother and her children at gunpoint after a license plate reader flagged their SUV as stolen. The actual stolen vehicle, a motorcycle, had the same plate number from another state. Police officials have said racial profiling did not play a role, though the drivers in all three cases were Black. (The license plate readers in these cases were not Flock devices, and the company said its systems would have shown more accurate results.)

Sixteen states have laws governing license plate readers, but most of them restrict government, not private, use. Even those efforts have come up short. In Vermont, one out of 10 license plate database searches by police broke the rules on how the system could be used, a 2018 state audit found.

When Flock installed 29 cameras in Dayton, Ohio, as part of a months-long trial for the police, residents were surprised and angry to see so many of them recording in the heart of the city’s Latino community — including outside a church where local immigrant families attend Mass and gather with friends.The cameras were later removed. Flock told The Washington Post that there was a “gap in communication” between the local communities and police.

The Paradise Hills opponents were right to be skeptical about a local crime wave. According to Jefferson County sheriff’s records shared with The Post, the only crime reports written up since September 2020 included two damaged mailboxes, a fraudulent unemployment claim and some stuff stolen out of three parked cars, two of which had been left unlocked.

“I wouldn’t exactly say it’s a hot spot,” patrol commander Dan Aten told The Post.

Schwartz, the EFF lawyer, said many of the neighborhood surveillance debates have shown hallmarks of a “national irrationality” around crime: though gun crimes went up last year, overall crime was down as part of a decades-long slide; the property crime rate has been cut almost in half over the past 20 years.

“Makers of surveillance technologies,” he said, “spend a lot of money telling police and the public that we have a serious crime problem, and the solution is what we’re selling.”

In the weeks after the Flock proposal, the infighting among neighbors in Paradise Hills — reflected in internal emails and text messages shared with The Post — reached a fever pitch.

Camera supporters griped that opponents were naive, penny-pinching Luddites standing in the way of community progress. And the critics griped that they were being transformed into a surveillance state thanks largely to one board member notorious for repeatedly — and, to them, unnecessarily — calling the police.

In June, the board’s vote to buy the Flock system passed 4-2. One member, Craig Southorn, said the camera debate had been the most divisive issue in his two years on the board, and — though he voted “no” because of the cost — he hoped the system might help finally bring his neighbors peace of mind.

“The risks and potential downsides of misuse and abuse of the information are very real,” he said. “But it’s also a fact of life that when you’re in the public, there’s probably a good chance that somebody, somewhere, somehow is recording it.”

The installation did not end the bitterness. Shortly afterward, a board member raking pine needles in his lawn began sparring with a camera critic and her husband walking their dog, shouting that she was a “crazy b—-” and threatening to pay her “a visit tonight,” a sheriff’s report states. The board member, who has since resigned, told deputies the woman had been “trash-talking” him about the cameras.

The cameras clicked on in August, a board member said. In the weeks since, the neighborhood hasn’t seen any reports of crime. The local sheriff’s office said it hasn’t used the Flock data to crack any cases, nor has it found the need to ask.

For now, the most lasting tributes of the skirmish are the two Flock scanners mounted above the neighborhood’s welcome sign. When volunteers went recently to paint the fences on Paradise Road, the cameras were there, recording away.

More Stories

Watch Adam Savage Go “Hands On” With the Original Enterprise From ‘Star Trek’ – Review Geek

Google Messages reactions about to expand in choices

Get a 2nd-Gen Apple Pencil for the Lowest Price Ever