As promised in the piece about 10Gbps Internet, I’ll explain here the differences between Dual-WAN vs Link Aggregation and how to set up each when applicable.

In most homes, both of these features can be unnecessary. They are nice to have but might not be worth the extra cost. And for that reason, you will not findDual-WAN or Link Aggregation in every Wi-Fi router.

But many routers support one of the two or even both.

For this post, I use an Asus RT-AX89X, which, like most high-end Asus home routers, comes with flexible network ports and both Dual-WAN and Link Aggregation. The router also has a ton of LAN ports to spare.

Consequently, if you have any Asus routers, you’ll find what I describe here closely applicable. If you use a different router brand with these features, the interface for the configuration might be different, but the general principles remain.

Most importantly, while these two features have lots of customization available in business and enterprise routers, they are generally available in home routers at the most basic level — they are easy to use enough. Keep that in mind.

Dual-WAN vs Link Aggregation: (Almost) totally two different things

I’ve gotten many questions where folks mentioned Dual-WAN and Link Aggregation as though they are the same.

While you can use Link Aggregation in a WAN (Internet) connection — that’s WAN Link Aggregation. The two are different in nature.

Let’s start with Dual-WAN.

Dual-WAN: It’s a matter of (extra) bandwidth vs speed

When it comes to the Internet connection — a.k.a the wide-area network or WAN — we often talk about speed in megabits per second (Mbps) or even Gigabit per second (Gbps).

Data transmission speeds in a nutshell

On a computer screen, each character, including a space between two words, generally requires one byte of data.

(So the phrase “Dong Knows Tech,” no quotes, requires at least 15 bytes, and likely more in reality since the formatting — such as capitalization and font — also needs extra storage space.)

One byte equals eight bits.

1,000,000 bits = 1 Megabits (Mb).

Megabits per second (Mbps) is the common unit for data transmission nowadays. Based on that, the following are common terms:

- Fast Ethernet: A connection standard that can deliver up to 100Mbps.

- Gigabit: That’s 1Gbps or 1000Mbps. It’s currently the most popular wired connection standard.

- Gig+: A connection that’s faster than 1Gbps but slower than 2Gbps. It often applies to Wi-Fi 6/E or Internet speeds.

- Multi-Gigabit: That’s multi-gigabit — a connection that’s 2Gbps or faster.

- Multi-Gig: A new BASE-T wired connection standard that delivers 100Mbps, 1Gbps, 2.5Gbps, 5Gbps, or 10Gbpsd, depending on the devices involved.

And that’s easy to relate to since we all want to know how fast our connection is. But speed and bandwidth can be two different things. Here’s a scenario:

Suppose you have a 500Mbps broadband connection. On one computer, you run a speed test and indeed get 500Mbps. At that same moment, if you do the same test on another computer, well, that one will get 0Mbps. More realistically, you’ll get 250Mbps on the 2nd computer, and the first computer’s test result will also be cut in half.

That’s because 500Mb is also the total bandwidth of your Internet pipe — the max amount of data the connection can deliver at any given time.

So to get two concurrent 500Mbps connections, we’ll have to have a Gigabit (1000Mbps) connection. Or you can get another separate 500Mbps line. And that’s where Dual-WAN comes into play.

Dual-WAN will not increase your Internet speed, but only the bandwidth. Specifically, if you have two separate 500Mbps broadband plans, you will never see the rate of 1000Mbps in a single test.

Instead, you’ll be able to get the full 500Mbps on two computers simultaneously. And that can be a good thing since no computer in the network can hog all the Internet bandwidth.

But that’s only the case when you load-balance a Dual-WAN setup.

Dual-WAN: Load-balancing vs failover

Load-balancing is when you use two WAN connections simultaneously to increase the bandwidth. For this reason, it’s most applicable when the two WANs share similar speed grades, such as when you have a Gigabit Cable plan and a Gigabit Fiber-optic line.

When you have two lopsided connections, load-balancing works, too, just not as effective. There are two scenarios:

- Equal bandwidth: That’s when you divide the bandwidth equally between the two WANs. That’s often referred o as 1:1 load balance. In this case, the slow WAN will get clogged up very fast while the fast WAN is hardly used.

- Proportionate bandwidth: That’s when you allocate the network’s Internet usage proportionately between the two WANs according to their speeds. For example, if you load-balance a 900Mbps WAN and a 100Mbps WAN (the former is 9x faster), you can make the first handle 90 percent of the network’s Internet bandwidth and leave the rest 10 percent to the second WAN. That’s a 9:1 load balance.

Depending on the differences between the two WANs, a proportionate load-balance setup might work out. However, in the extreme cases, chances are there’s hardly any case you’d need the 2nd WAN.

Since load-balancing requires extra resources from the router — it has to deal with two WAN connections at all times — in the case of severe lopsided WAN connections, like the one mentioned here, it’s best to use them in the failover configuration.

(This is also my case, I have a 10Gbps Fiber-optic line and a Gigabit Cable plan.)

In failover Dual-WAN, you pick the faster WAN as the primary and the slower one as the secondary. The former is in use by default, and only when it becomes unavailable will the latter kick in. This keeps the network from being disconnected from the Internet.

Failover Dual-WAN is great for environments where you can’t afford to go offline while the primary WAN is down.

In reality, there’s still a very brief outage before the switch. And that brings us to the next part on how to adjust the parameters in a Dual-WAN connection.

Dual-WAN setups: Understanding the standard settings

Setting up a Dual-WAN connection is simple. It’s the same as setting up a single WAN connection plus another one. Here are the general steps on a supported router:

- Identify the network port used for the Primary WAN and another for the Secondary WAN. For this post, I’d use the 10Gbps Base-T Multi-Gig port for the former and the router’s default Gigabit WAN port for the latter.

- Connect the WAN ports to their respective internet sources. In my case, they are the 10Gbps Sonic Fiber-optic ONT and the Comcast Cable modem.

- Log in to the router’s web interface, go to the WAN (Internet) section, and set up the Dual-WAN accordingly. In my case, I tried both Failover and Load-Balance.

And that’s it. We’re done with the hardware part. It’s easy enough.

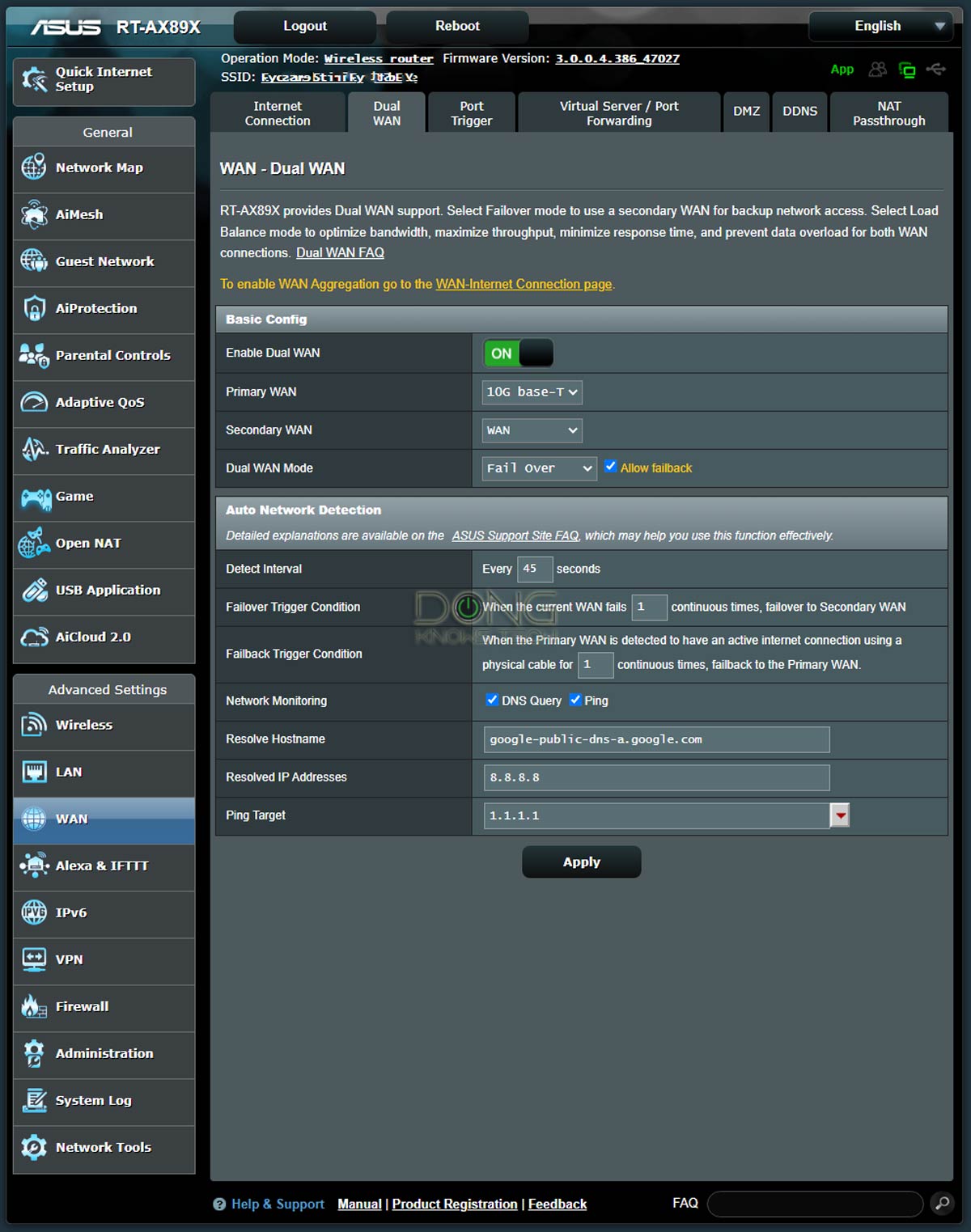

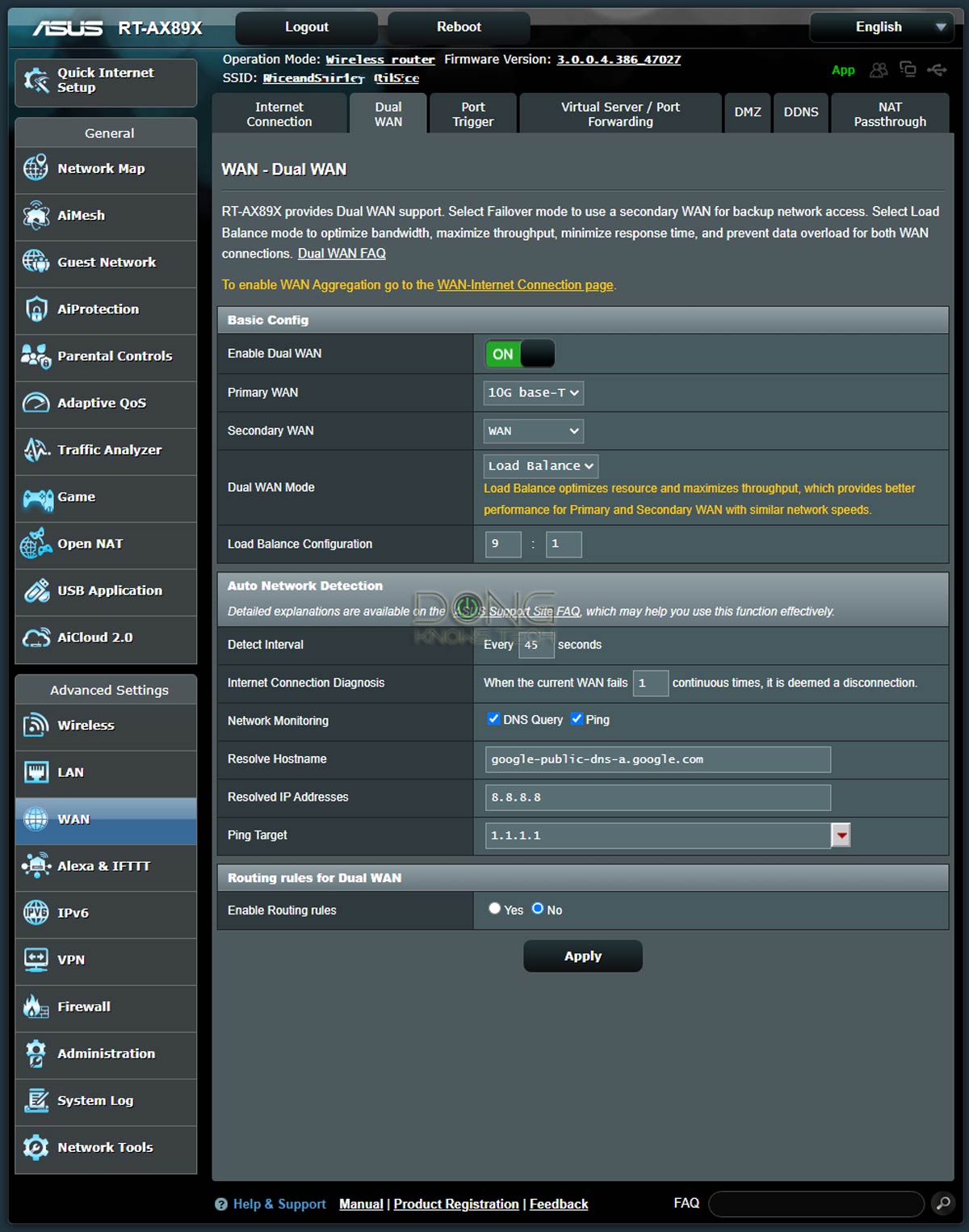

With that, let me explain a few basic settings in a Dual-WAN setup via the interface of an Asus router. (Again, if you use a different brand, the wordings, and the settings should be similar.)

- Basic configurations:

- Primary WAN: This is the main (faster) Internet connection.

- Secondary WAN: The secondary (slower) Internet connection.

- Dual-WAN Mode: Either Load Balance or Failover.

- Auto Network Detection: This part includes the setting for the router to know when a WAN connection is unavailable and behave accordingly. Specifically, in a Failover setup, it will switch to the secondary WAN, and in a Load-Balance setup, it’ll use the available WAN 100%. This section includes the following parameters:

- Detect Interval: The frequency the router will check a WAN connection for its online status. It’s best to set this number to be 30 seconds or longer. A lower value might cause the router to overwork.

- Failover-only settings:

- Allow fallback: Allow the router to move back to the primary WAN when it becomes available when the secondary WAN is in use.

- Failover Trigger Condition: The number of consecutive times the primary WAN appears unavailable before the router switch to the secondary WAN. Multiply this number with the value of the Detect Internal to know how long the router will appear offline before it switches to the secondary WAN.

- Fallback Trigger Condition: The number of consecutive times the primary WAN appears available before the router switch back to it. Multiply this number with the value of the Detect Internal to know how long the router keeps using the secondary WAN before it moves back to the primary WAN.

- Network Monitoring: The methods used for the router to find out if a WAN connection is online. There are two options:

- DNS Query: It’s fast and safe. However, there’s a chance that the information is cached and therefore not accurate — you might want to set the Trigger value mentioned above to be higher than 1. You need to pick a domain (Resolve Hostname) and an IP address (Resolved IP Address) that belongs to that domain. You can select any of your choosing. Just make sure you use one that has a high uptime. When this domain is down, your router will think your WAN is unavailable. The value in the screenshots is those of Google’s free DNS service. You can use them.

- Ping Target: An IP address or domain that the router can send a Ping command. This method is effective when it works. However, some domains might block the ping command, especially when that happens frequently. Keep the Trigger value at 1 in this case.

- Load-Balance-only Settings:

- Load-Balance Configuration: This is the proportionate bandwidth allotment for the two WANs as mentioned above. You can enter from 1 to 9 for each WAN depending on how they are different in terms of speeds.

- Enable Routing rules: You can set rules to make a certain device within the network access a particular public IP address via a specific WAN connection (primary or secondary). Generally, a router supports about 30 such rules, but there’s no need to use them unless you have special purposes.

In my experience, when you have two lopsided WAN connections, like in my case, it’s best to use the Failover setting.

I’ve used that for a few weeks now, and it has panned out well. Among other things, I could remove one WAN connection from my personal router and connect it to a test router without causing any issue within my home network.

For most homes, though, Dual-WAN might not be worth the cost, but in this case, two is definitely better than one.

With that, let’s move on to Link Aggregation.

Link Aggregation: It’s all about local speed

Link Aggregation, also known as bonding or Link Aggregation Group (LAG), is more straightforward than Dual-WAN.

In a nutshell, it’s when you combine two network connections (ports) into a single link.

Link Aggregation, in business and enterprise applications, has a lot of flavors, but in-home usage, the most popular is the 802.3ad standard.

This standard is most applicable to Gigabit ports. Specifically, you can combine two Gigabit ports into a 2Gbps connection to deliver the combined bandwidth and Failover capacity. If one of the two ports fails, you still get a Gigabit connection from the LAG.

Link Aggregation is available on both the WAN and the LAN sides. But in either case, it’s always about the local network — it’s never available in the service line.

In any case, a LAG connection is awkward and messy because it requires two network cables. By the way, for Link Aggregation to work, you need a supported router (or switch) and supported device — most NAS servers have it.

WAN Link Aggregation: Relatively rare

On the WAN side, Link Aggregation is when you use two network ports on a terminal device (most likely a Cable modem) to connect to two ports on a router as a 2Gbps connection.

It’s somewhat a “cheat” way for an Internet service provider to deliver 2Gbps broadband to its customer. Nowadays, with Muti-Gig routers and modems being commonplace, WAN Link Aggregation is no longer a popular choice.

Personally, I’ve never used WAN Link Aggregation.

LAN Link Aggregation: It’s a cool bonus

On the other hand, I’ve used LAN Link Aggregation for years.

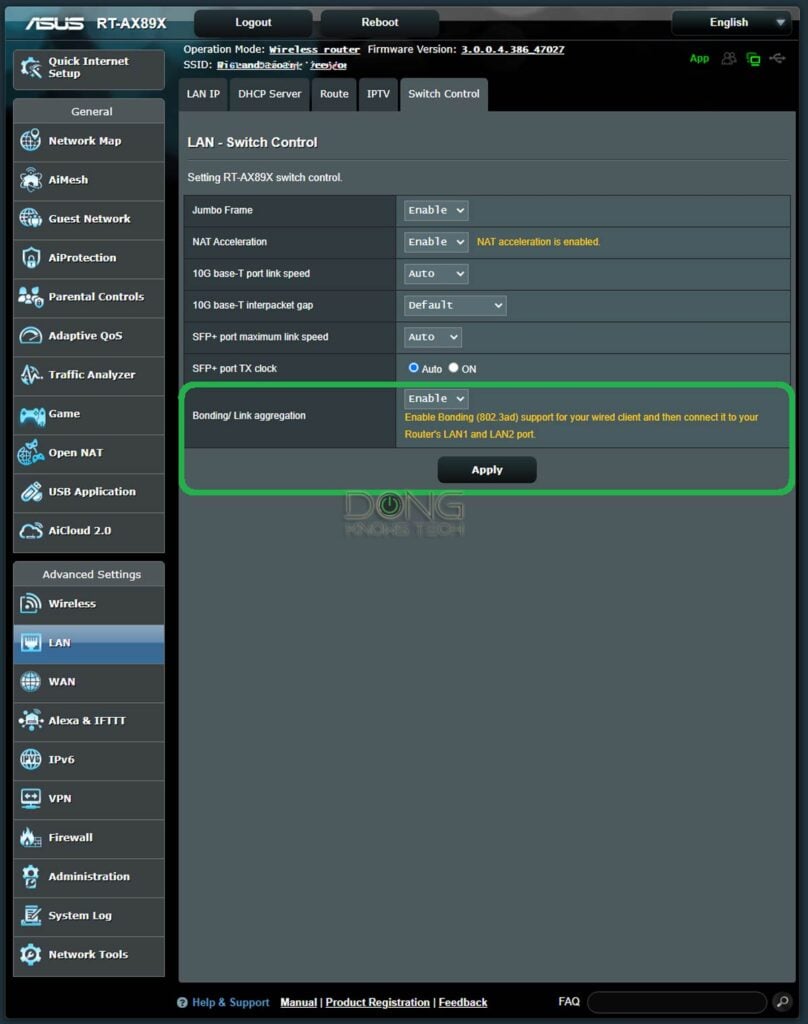

Indeed, most Asus routers have these features. You can combine its first and second LAN ports into an 802.3ad LAG, and virtually all Synology NAS servers with two or more LAN ports also support 802.3ad Link Aggregation (and other LAG flavors.)

If you have both, the setup steps are easy:

- Create the LAG on the router using its web interface as shown in the screenshot above, using LAN1 and LAN2.

- Use two network cables to connect the router’s two LAN ports to the server.

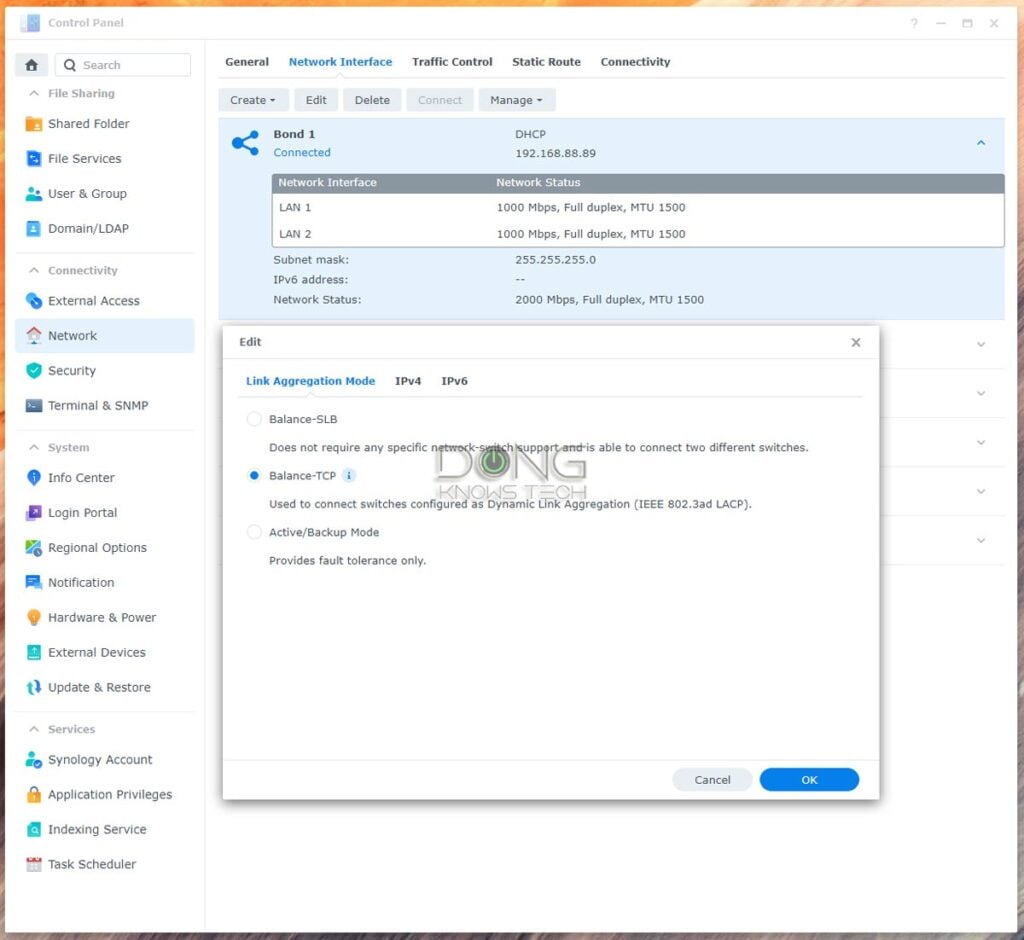

- On the server, go to the Network section of the Control Panel and create a bond using the two LAN ports using the Balance-TCP mode, which is a different name for 802.3ad LAG.

Mission accomplished.

A couple of years ago, before the age of Multi-Gig, a LAG connection used to be the only easy way to achieve a multi-Gigabit connection. In any case, a LAG-enabled server can simultaneously deliver two full Gigabit connections to two Gigabit clients.

And that has been the case in my experience. Link Aggregation is a pure bonus.

Dual-WAN vs Link Aggregation

Again, to recap.

Some routers can simultaneously support two Internet sources, such as Cable and Fiberoptic. That’s a Dual-WAN setup.

In this case, it can have two WAN ports (or it can turn one of its LAN ports into a WAN) or use a USB port as the second WAN to host a cellular dongle.

A Dual-WAN setup increases your network’s chance to remain online during outages (Failover), or you can simultaneously use the two Internet connections to get more bandwidth (Load-Balance).

Link Aggregation, also known as bonding, is where multiple network ports of a router aggregate into a single fast combined connection. Typically, you can have two Gigabit ports working in tandem to provide a 2Gbps link.

Many routers from known networking vendors have this feature. You can have Link Aggregation in WAN (Internet) or LAN sides.

The former requires a supported modem. And in the latter, your wired client also needs to support it. Most NAS servers do.

Apart from delivering more bandwidth, a Link Aggregation connection is also capable of failover.

While Dual-WAN and Link Aggregation are both about increased bandwidth, they are different in that the former is about using two distinctive broadband connections simultaneously while the latter is about using two identical local connections together as one.

The takeaway

Again, while neither Dual-WAN nor Link Aggregation is a must-have in most home networks, they are a bonus when you can use them.

Dual-WAN requires extra monthly data cost, so it’s not feasible or necessary. However, many routers support LAG and if you happen to have a server that also supports it, there’s no reason why you shouldn’t get an additional network cable and try it out.

More Stories

Essential Things To Include In Your Skincare Routine

4 charts that show just how big abortion won in Kansas

Here Are The Best 15 Apps For Learning Science